THE night before a health inspector came to my apartment, I had a brief nightmare about a grim-faced woman in a lab coat who crawled across my kitchen floor with a pair of tweezers. So when it came time to greet the actual inspector, Beth Torin, one of the first things I uttered to her had a slightly unaccommodating air about it: “Your presence in my home terrifies me.”

Ms. Torin, a forceful, chatty woman in her late 30s, reached into her bag to produce her badge and said, “My mother tells me the same thing.”

Some of us have been thinking about kitchen sanitation with greater frequency ever since July, when the New York City health department started requiring restaurants to post letter grades signifying their inspection scores. (An A denotes zero to 13 points worth of violations; B, 14 to 27; C, 28 or more.)

But has this increased awareness of restaurant cleanliness had any trickle-down to our own kitchens? The societal function of posting health-code violations in public would seem to have the same double edge as that of gossip columns: in some instances, these broadcasts humiliate sinners into better behavior; but in others, they make the sins look normal, and thus open the floodgates.

Eager to find out where my West Village kitchen falls on the continuum, I called the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and arranged for a restaurant inspector to visit at noon last Thursday. I asked them to overlook any stipulations that would not apply to a home, like the signs in restrooms that remind employees to wash their hands. Restaurants get no warning before an inspection; so, to handicap myself, we decided that Ms. Torin would arrive one hour before I was to serve an elaborate lunch to four friends.

I had 27 hours to prepare, or should I say to obsess. That my wholly average-seeming level of cleanliness was to be rated while I was cooking for guests filled me with a kind of terror; my brain dredged up the words dance recital, underrehearsed, overweight, leotard. The inspection information on the health department’s Web site was largely unsurprising. But it did prompt me to remove a light bulb over my stove that was not “shielded or shatterproof.” Then I scrubbed and scoured for nine hours.

Having formulated the theorem, “It can’t be a violation if it doesn’t exist,” I removed seven garbage bags’ worth of opened foods and assorted flotsam from my kitchen. I used antibacterial wipes on any surface my cats may have walked on. After sleeping for an hour, I awoke at 12:30 a.m. — the grim-faced woman with the tweezers — and cleaned for another hour. The next morning, uncertain how much of my environment would fall under the inspector’s purview, I sponged four dust-saddled walls in my building’s stairwell, and bagged and discarded a wet mohair rug that had mysteriously appeared on the stoop.

Ms. Torin’s arrival brought three surprises — she was 35 minutes late; she was chatty, with a lot of short blond corkscrew curls but no tweezers; and she was wearing heels and a gray pantsuit. (Inspectors generally wear a uniform, but Ms. Torin sometimes inspects in her office-wear.) She first produced a palm-size meter from her bag, to check carbon monoxide levels inside and outside the apartment and thus make sure my exhaust hoods were working. Satisfied, she then asked if she could wash her hands. I proudly pointed to my kitchen sink, where I’d fastidiously placed canisters of antibacterial wipes and liquid soap.

I was dismayed to hear: “You’re not allowed to wash your hands in the kitchen sink. I coughed when I came in the door. Who knows where my hands have been?” Wherever they’d been, the germs they carried with them were now in the same sink I use to rinse lettuce.

If the sleigh ride that was this inspection had just been given its initial push down the slope, it then proceeded to plunge, luge-like, down a sluice gate of detritus-flecked squalor. Most disastrously (that is to say, 38 points’ worth of disaster), Ms. Torin determined that my refrigerator — which, despite some dripping condensation during the summer, has always been perfectly adequate for my needs — was warmer than the required 41 degrees, as was the food inside. I didn’t know I had this problem because I don’t keep a thermometer in my fridge (2 points).

These struck me as mostly legitimate violations, as did my broken meat thermometer (8 points). But then Ms. Torin started rifling off a series of less galvanizing concerns: the towels I use to wipe my counters were not soaking in a sanitizing solution (5 points), my cutting board had many tiny nicks and grooves, and thus may breed bacteria (2 points). I realized that I needed to start playing hardball if I wanted to avoid earning the nickname Typhoid Henry.

When, on seeing cat food in a cabinet, she asked if I had a cat (5 points), I said yes but did not reveal that my boyfriend and I actually have two (10 points). Then I stealthily whisked my lovingly wrought appetizer — Thai shrimp and basil summer rolls — out into the living room before Ms. Torin could nail me for harboring under-refrigerated shellfish (8 points). As they say on television these days: I’m not here to make friends, I’m here to win.

In the meantime, my guests had started arriving. Ms. Torin told my friend Liz, “I’m making sure that your meal is safe.” Liz replied, “I wish you were here every time I came.” My friend Mark bore a bouquet of fluffy white hydrangeas, saying, “I thought they suggested the immaculate.”

Simultaneously, I was whipping up two corn soufflés. The trifecta of guest arrival, soufflé preparation and government-backed humiliation was, for this host, a lake of fire. Imagine that your war crimes tribunal is being filmed while you broil scallops. As guests spilled in and egg whites were whipped, Ms. Torin continued zealously snooping around the kitchen, brandishing a tiny flashlight to look for rodent excreta, and telling me that I should sand down my aged cutting boards and retrieve ice from my freezer with a scoop. I grimace-smiled like a polar bear at a world climate summit.

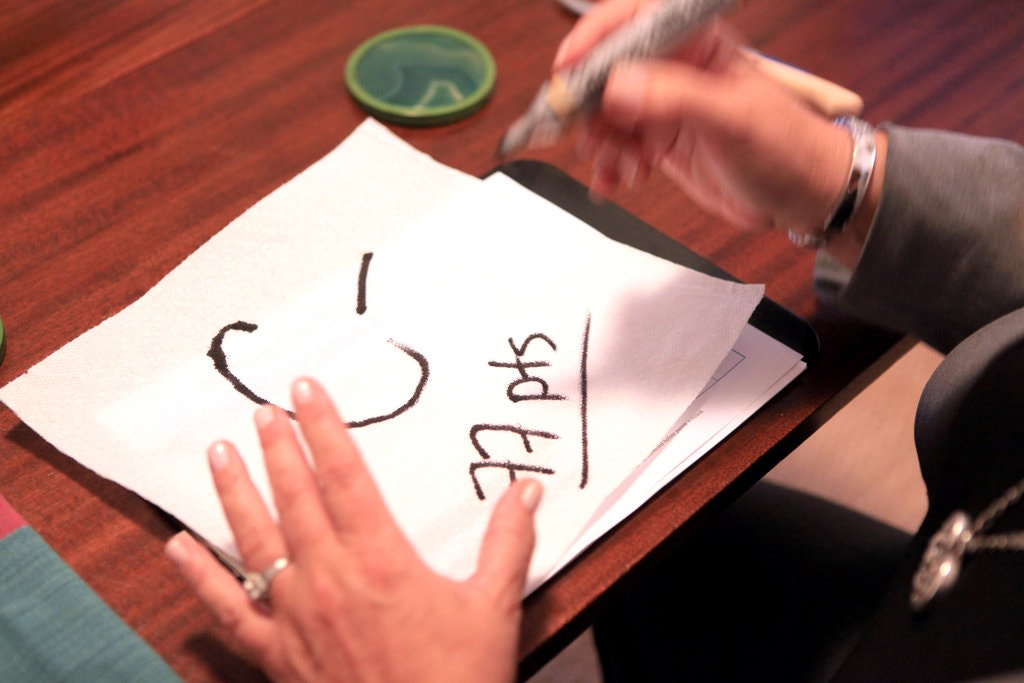

Ms. Torin totted up my violations on a worksheet: 77. Flunkadelic. She offered some faint praise, including the heart-warmers “Your covered garbage can is great” and “You didn’t obstruct me.”

If a restaurant gets a score higher than 14, an inspector returns for a second visit in about two weeks. The restaurant can post this second grade, or a sign that says “Grade Pending.” About three weeks later, a representative from the restaurant appears before an administrative tribunal, where the grade is arbitrated and finalized.

But, Ms. Torin said, were my home a restaurant, my lack of adequate refrigeration would have resulted in more dramatic action. “We would make a decision very quickly,” she said. I raised my eyebrows in a manner that said either, “And would kindness prevail?” or “Should I get the vial of Seconal now?”

Uncharacteristically demure, Ms. Torin replied, “I don’t want to depress you because you have guests here.”

That my friends, apprised of my rating, then consumed large quantities of the food I had prepared says everything to me about why I have chosen these particular individuals to be in my life. Their forbearance reminded me of Mrs. John Gotti’s statement about her husband: “All I know is, he provides.”

The next day, I spoke by phone with Ms. Torin, who was concerned she had been too hard on me. She had docked me for a few things specific to restaurants — e.g., 5 points for my not wearing a head covering — and she was feeling more charitable about my refrigerator.

“I can see you don’t cook a lot,” she said. “You didn’t have much food, but a lot of wine.” Deciding not to explain that I’d nervously divested my fridge of two garbage bags’ worth of items before her arrival, I instead tried to impress upon her the dictates of the go-go bohemian life, where the refrigerator is considered full if it contains a lemon peel and a jar of olives. She said she had a new score for me.

But before she gave it to me, I leveled with her: “Over the weekend, I’m going to fix most of these violations, which should be easy. But I’m not going to stop washing my hands in the sink, and I’m not soaking my wiping towels in bleach, and I’m not killing my cat. What I’m saying is, I’m a 20 at heart. Knowing that, would you personally, being both neurotic and a food safety inspector, ever come to eat at my 20?”

Ms. Torin said: “Totally honestly? I wouldn’t eat in your apartment because you have a cat.”

We resumed a discussion we’d had about how cats can blithely go from litter box to tabletop or kitchen counter, transporting bacteria. But we kept talking, and she soon changed her tune. “You know what?” she said. “I’ll give you the cat if you swear you’ll wash your hands in the bathroom. Then I’d come over. You’ve got to eat somewhere.”

Post-inspection, I’ve made a few changes. I’ve lowered the temperature of my refrigerator. I’ve bought a new meat thermometer. I’ve nicknamed the friskier of the two cats Five Points. I’m thrilled that public places of eating are held to higher standards than homes, and that the full fruition of these high standards results in the first letter of my last name. But when it comes to my own environs, I’m hoping my patrons understand that I’m no Hester Prynne. At 41, I’m still a C. That’s C for cleanish.

Pass or Fail, Some Health Basics for the Kitchen

Some of the things health department inspectors watch for in restaurants are worth keeping in mind at home. Among them:

Make sure to clear the sink of dishes and pans before washing hands, and use different towels to dry hands and cookware. Have liquid soap and paper towels in your bathroom for hand-washing.

Make sure your cutting boards don’t have nicks and grooves where bacteria can grow. If they do, you can sand or replace them. Bacteria can also thrive inside cracks in floor tiles and wood countertops.

Make sure your refrigerator is working properly and keep it on a cold setting.

Don’t let food linger on countertops a long time before cooking and serving it.

Keep pets off countertops and dining tables.

Damp dish towels can breed bacteria. Keep them clean and dry, or use paper towels.